Before the season, Cheshire’s guard hierarchy looked set. LaQuincy Rideau was back — returning after a season away, a homecoming for the leader of the Cheshire team that had pushed the 777-era Lions two years earlier. Pat Robinson was meant to play off him.

But within weeks, that balance has shifted. Rideau’s minutes have dipped, Robinson is the more constant presence, and Jaxon Brenchley and Tobias Cameron have filled the gaps around them — Brenchley steadying the offence, Cameron tightening the defence. What began as a question of hierarchy has become one of chemistry, of how four backcourt players with distinct identities fit together on the floor.

Driving Downhill, Again and Again

In the SLB Show’s Cheshire season preview, basketball scout Louie Hills was describing Pat Robinson when he said: “His one thing is getting to the rim.” That still holds true. Robinson’s entire game bends toward that single action: driving, then finishing or creating. He wants to create downhill every time he touches the ball, and when he’s allowed to, he looks electric.

But his game is also narrow. In a league where most small guards survive by stretching the floor from behind the three-point line, Robinson lives almost entirely inside it.

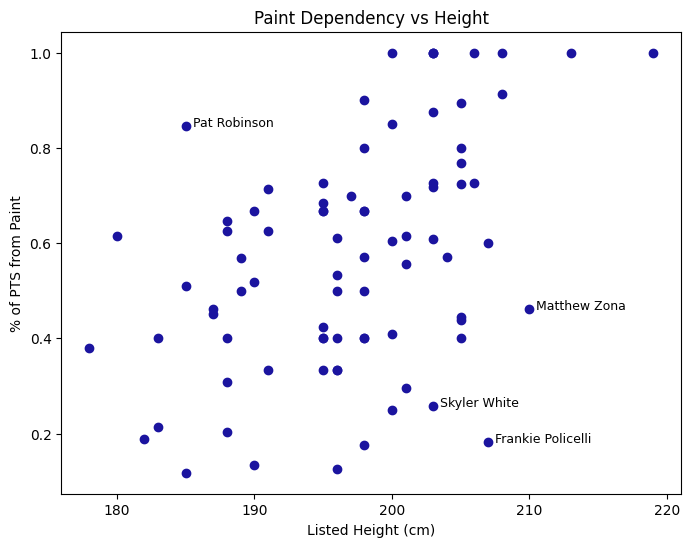

*Only players with a listed height on the SLB website who have scored more than 10 points this season are included.

84% of Robinson’s points from field goals have come from inside the paint; he sits alone in the top-left corner — a guard whose scoring map looks more like a centre’s. He’s made four of his fifteen attempted threes, and his 64 per cent free-throw percentage emphasises how limited his range really is. Even his assist-to-turnover ratio (1.40) shows more function than invention.

Despite those limits, Cheshire’s roster is built in a way that lets Robinson thrive. This isn’t a team that punishes paint-only guards. Two of their main frontcourt players — Skyler White and Frankie Policelli — both shoot from deep, stretching the floor where Robinson can’t, appearing in the bottom-right corner of that same chart. When they pull defenders out of the lane, he drives into the space they leave behind. It’s a design that turns his lack of range into a feature rather than a flaw.

Order and Chaos

That sense of balance carries into the backcourt, where each guard plays to a different rhythm. LaQuincy Rideau ranks fourth in the league in steals per game (2.3), playing on the edge — constantly looking to jump passing lanes and push the tempo. His aggression fuels Cheshire’s energy but also brings risk, reflected in his near one-to-one assist-to-turnover ratio (0.95).

Jaxon Brenchley sits at the opposite end of that spectrum. He ranks among the league leaders in assist-to-turnover ratio (5.67) — a mark of calm, controlled precision. Tobias Cameron provides the anchor between them, taking on tough defensive match-ups and leading the group in rebounds (5.2 per game).

Together they define the balance of Cheshire’s backcourt — Rideau creating chaos, Brenchley supplying order, Cameron holding the line. Within that structure, Pat Robinson can attack without hesitation, trusting the balance around him to hold.

Simplicity as a Strength

Robinson doesn’t need to be the lead guard to matter. His value comes from knowing exactly what he brings — speed, pressure, intent — and applying it relentlessly. He plays fast, direct basketball: attacking the rim, collapsing defences, forcing reactions. He never complicates his game.

Cheshire have built a roster that allows him to be singular — to focus on the one thing he does better than almost anyone else. In a sport full of players trying to prove they can do it all, Robinson shows the power of doing one thing with complete conviction.