Ages 18 to 22 are a decisive phase in a basketball player’s development. This is when players begin the transition from prospect to contributor, completing their physical growth and learning to survive possessions at higher levels rather than dominate them at lower ones.

At this stage, development comes from minutes, not just training. Playing through mistakes in competitive environments matters more than preparation alone.

The question is whether the British domestic pyramid provides enough of those minutes. Looking at how playing time is distributed in the top two men’s leagues suggests it does not.

Minutes by Age Cohort

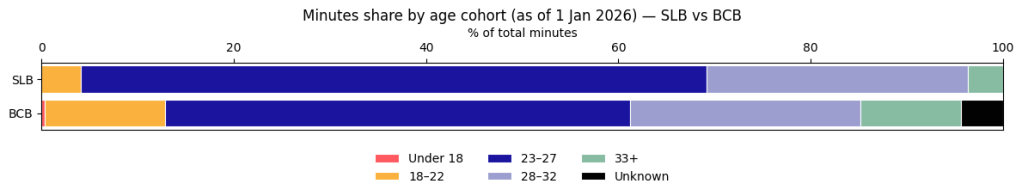

The charts below show minutes played by age group in Super League Basketball and British Championship Basketball. Players are grouped by year of birth, with cohorts reflecting common stages of physical and professional development.

The 18–22 group captures players in the traditional transition window from youth basketball into the senior game. The 23–27 group reflects the early professional years, when players are expected to establish themselves as rotation-level contributors.

*Player ages as of 1 January 2026 compiled from public sources. Where dates of birth were unavailable, ages were estimated using publicly available information.

In SLB, minutes are concentrated among players who have already moved beyond the development window. Nearly two thirds of all minutes are played by athletes aged 23–27, with a further large share taken up by players in older cohorts.

Players aged 18–22 barely appear. With rare and highly specific exceptions, SLB is built to prioritise immediate contribution over long-term development.

BCB shifts the distribution slightly. The league gives more time to players aged 18–22 than SLB does, but overall minutes remain concentrated among older age groups.

Across the top two tiers, the transition years still sit largely on the margins. Even where the second tier expands opportunity, it does so under the same pressures to win games and justify short-term decisions as the level above it.

Where Development Minutes Actually Exist

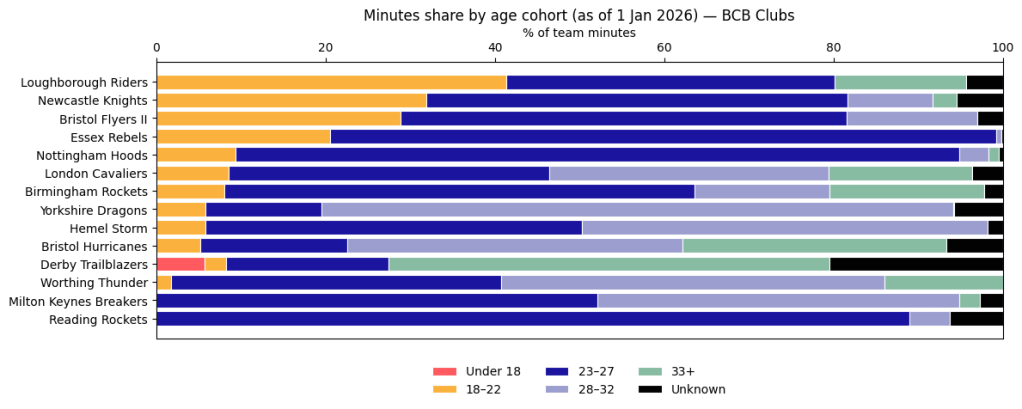

League-wide totals hide how unevenly development minutes are distributed. When British Championship Basketball is broken down by club, the variation becomes clear.

A small number of teams account for a disproportionate share of minutes played by 18–22 year olds. What links those teams is insulation.

Essex Rebels and Newcastle Knights are university-linked programmes. Bristol Flyers II operate as a second team. Loughborough Riders are university-linked and also function in practice as a feeder programme for Leicester Riders’ SLB club.

In each case, squad construction allows a higher tolerance for younger rotation players. Short-term wins are not the sole measure of success. Minutes can be given, mistakes absorbed, and development allowed to happen without destabilising the programme.

Elsewhere, opportunities for players in the transition window are far more limited. Without room to absorb inconsistency, clubs tend to default to older, safer options.

Missing Years in the Pro Pathway

Taken together, Britain’s top two men’s leagues function as competitions for players who are already ready. They reward reliability more than potential.

That leaves a gap between youth basketball and established professional roles, and very few minutes to occupy it.

Those minutes don’t disappear because no one believes in young players. They disappear because there is nowhere safe for them to exist.